By Peter Gleick, President

July 8, 2013

As most people now know, hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is a method for enhancing the production of natural gas (or oil, or geothermal energy wells). Fracking involves injecting fluids – typically complex mixes of water and chemicals – under high pressure into wells to create cracks and fissures in rock formations that improve the rates of production.

Whether you support or oppose fracking depends on many complex factors: the economics of the practice, perceptions about the implications for national security of relying on domestic or imported energy, the consequences for climate change from the emissions of different amounts of greenhouse gases from different energy strategies, the positive and negative implications of fracking for employment and quality of life in rural communities, and the scientific evidence about the environmental consequences of the practice, including risks to water availability, water and air quality, and local ecosystems.

Some of the most significant environmental concerns associated with fracking are related to impacts on water. In 2012, the Pacific Institute released a major study on these water-related risks.

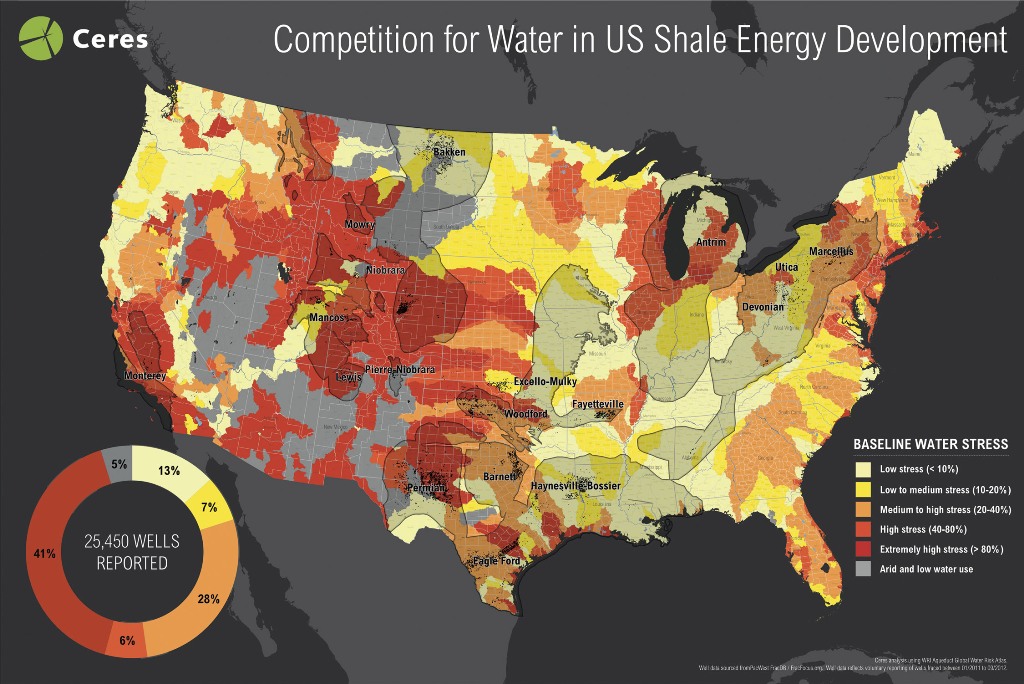

These risks include growing competition for limited water resources; the production of large volumes of contaminated wastewater that comes up with the oil or gas and must be treated, reinjected, or otherwise safely stored; truck traffic and its impacts on the water quality of streams; spills and leaks; and the risks of groundwater contamination from the drilling and fracking process or from surface seepage of improperly handled wastewater. Ceres recently released a map showing that many fracking operations are occurring in regions of the U.S. where water stress is already a real problem.

The Pacific Institute analysis concluded that a lack of credible and comprehensive data and information makes it much more difficult to identify or clearly assess the key water-related risks associated with hydraulic fracturing and to develop sound policies to minimize those risks. While much has been written about the interaction of hydraulic fracturing and water resources, the majority of this writing is either industry or advocacy reports that have not been peer-reviewed. As a result, the discourse around the issue is largely driven by opinion. Only by comprehensive and careful independent testing and monitoring is it possible to assess the full environmental and public health risks of fracking and identify strategies to minimize these risks.

This is particularly true for groundwater contamination, which is hard to measure, hard to monitor, and hard to track. For a while, proponents of the controversial practice of hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” have claimed there was little or no evidence of real risk to groundwater. But as the classic saying goes: “the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” of a problem. And the evidence that fracking can contaminate groundwater and drinking water wells is growing stronger with every new study.

In fact, even with the limited research done to date, there is clear scientific evidence that fracking not only can – but already has – led to groundwater contamination, including a new study recently released. As far back as 1984, the USEPA reported on a case in which hydraulic fracturing fluids and natural gas from production operations contaminated a groundwater well in West Virginia, “rendering it unusable.” More recent studies by the US EPA and then the US Geological Survey found groundwater contamination in wells in Pavillion, Wyoming. Studies (here, and here, and here) in the Marcellus Shale region of Pennsylvania found both increased risk for, and evidence of, contamination associated with fracking operations in the form of chemical contamination. A Canadian groundwater contamination report described a “hydraulic fracturing incident” in 2011 in which errors in well drilling and management led to the release of fracking chemicals into groundwater including isopropanolamine, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, petroleum hydrocarbons, and more.

This growing evidence of a real threat to water resources makes it all the more disturbing to learn that the US EPA is halting its own independent assessment of groundwater contamination from fracking in the Pavillion gas fields of Wyoming and even worse, turning that research over to a project funded by the fracking company itself. This is not how independent research should be done.

Far more and better research is needed, and public agencies must demand that monitoring data be independently collected, analyzed, and publicly released. But the evidence already available shows that fracking can threaten our water resources. We do not know if fracking efforts will continue to expand at the rate of recent years, or if new evidence of impacts will lead to changes in regulatory requirements and oversight, or if other national interests such as climate policy or efforts to promote non-carbon energy sources will alter the push for fracking. But no smart energy policy can be made if we turn a blind eye to the risks, fail to pursue comprehensive independent science, or even worse, deny the science and the evidence already available to us. Identify the real risks, share the science in a transparent manner, debate the implications in public and open forums, decide on appropriate public policy, and move forward.

Pacific Institute Insights is the staff blog of the Pacific Institute, one of the world’s leading nonprofit research groups on sustainable and equitable management of natural resources. For more about what we do, click here. The views and opinions expressed in these blogs are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect an official policy or position of the Pacific Institute.

Also, GHG emissions of natural gas needs to be considered. One person’s view: http://canadianenergyissues.com/2013/07/24/nrdc-feigns-outrage-over-1-2-billion-tons-of-carbon-from-oil-sands-supports-50-times-as-much-from-gas-fired-generation/