By Peter Gleick, President

In the past few weeks, I have had been asked the same question by reporters, friends, strangers, and even a colleague who posts regularly on this very ScienceBlogs site (the prolific and thoughtful Greg Laden): why, if the California drought is so bad, has the response been so tepid?

There is no single answer to this question (and of course, it presumes (1) that the drought is bad; and (2) the response has been tepid). In many ways, the response is as complicated as California’s water system itself, with widely and wildly diverse sources of water, uses of water, prices and water rights, demands, institutions, and more. But here are some overlapping and relevant answers.

First, is the drought actually very bad?

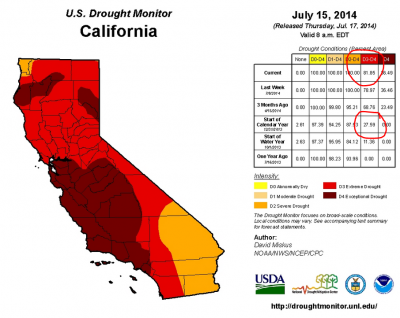

Even this question is complicated. If you look at the well-known Drought Monitor for California weekly maps, the answer is clearly “yes.” 80% of the state is in “extreme” to “extraordinary” drought and 100% of the state is in “severe” drought or worse. Other indicators also show the severity of the drought. This year will be one of the driest on record, as was 2013. Reservoirs are at record low levels. Deliveries of surface water to some farmers are lower than at any time in recent history. Streams are drying up and fisheries are being devastated.

Yet water still comes out of my tap, in unrestricted amounts and superb quality, at a reasonable price. And this is true of every resident in the state: drinking water supplies have not been affected, especially for the vast majority of the population that lives in cities of the San Francisco Bay area, Central Valley, and southern California.

While there will be some adverse impacts of some farmworkers and farmers, the overall agricultural sector will not have a bad year. Some farmworkers will be out of work this summer and fall, some farmers will be forced to fallow land because of the lack of water, and others will have higher costs associated with the need to replace surface water shortages with temporary groundwater pumping. But initial estimates from the University of California, Davis, the agricultural community as a whole will not see very large losses – a drop of perhaps 4% or so of normal farm revenue. It might be more; it might be much less. We won’t know until the end of the growing and harvest seasons.

In effect, despite our continuing water wars, the State of California’s economy has become largely insulated from the effects of short-term drought – even droughts of a few years. The agricultural sector, which consumes 80% or more of the water that humans use here, only produces $40 billion out of a total gross state product of over $2 trillion – 2 percent.

Has the response to the drought been tepid, and if so, why?

In January, Governor Brown declared a drought emergency. Terrific. That was the right thing to do. But it was not followed by any systematic statewide communications effort, any requirement for mandatory cutbacks, or any comprehensive information on how homeowners or businesses could save water. Other than an occasional billboard urging people to stop wasting water, or an occasional newspaper article about the drought, I have gotten little or no information from my water utility urging (or requiring) me to cut my water use, no detailed information telling me what I can do to save water, and no imposition of mandatory restrictions, except in a few small areas.

The Governor, at the same time, announced the availability of emergency funds of up to nearly $700 million for drought response. Yet now, half a year later and in the hottest, driest part of the year, a tiny fraction of that money has been spent, and very little on the most effective strategies for saving water: rapid and immediate conservation and efficiency programs to help farmers swap out inefficient irrigation technologies for modern efficient ones, or to get homeowners to permanently remove lawns or inefficient toilets, showerheads, and washing machines – to name just a few proven, cost-effective strategies.

Some water utilities don’t like to impose drought restrictions because they have still failed to meter 100% of their customers, so there is no way to measure or monitor demands for savings. Or they fear that conservation efforts simply cut revenues, which force them to raise rates to cover their operating expenses – an action that sours customers on further conservation efforts. (This does happen, but it is a failure of utilities to implement effective water rate structures that can encourage conservation while still satisfying revenue needs: see here for information on strategies to avoid this).

Some farmers have “senior water rights” and will get all or most of the water they need this year. These farmers have no incentive to conserve water or use it more efficiently – and the media and the public do not hear from them. Instead, the public only hears from junior water-rights holders who have posted highly visible signs along Highway 5 in the Central Valley decrying the “Congress created dust bowl” or other catchy phrases that try to place political blame for natural events. These actually come from a tiny part of California’s agricultural community who know that they cannot get all of the water they want (as junior water rights holders), even in normal water years, because the state has given away far more water than nature reliably provides.

So, for now, we muddle through with mostly voluntary exhortations to cut water use, some new mandatory penalties for egregious water wasters (though even these mandatory penalties will be largely unenforced and largely ineffective at reducing water waste), and a lot of wishful thinking that El Niño will bail us out next year.

That could happen. But it might not. If next year is also dry, the shit is going to start to hit the fan. Our reserves and marginal sources of water are gone or going. Our reliance on groundwater overdraft cannot continue without destroying aquifers and streams that depend on groundwater flow. The richest farmers and communities will begin to pay (as they are starting to now) premium prices to buy water from other farmers or to take advantage of loopholes that exempt groundwater from regulation, monitoring, and management, at the expense of poorer farmers and communities who cannot drill million-dollar wells. And more and more people will be at risk of waking up, turning on the tap, and getting nothing but air.

In short, the tepid response will turn into panic and pressure to take actions, even if those actions are inappropriate (like letting fisheries and ecosystems die) or could have been avoided had we done the smart things we should have done earlier.

Pacific Institute Insights is the staff blog of the Pacific Institute, one of the world’s leading nonprofit research groups on sustainable and equitable management of natural resources. For more about what we do, click here. The views and opinions expressed in these blogs are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect an official policy or position of the Pacific Institute.