By Cora Kammeyer

The first fall storm is rolling through the San Francisco Bay Area this week, marking the beginning of the rainy season. While this may mean a reprieve from this season’s wildfires, it also means there’s a new risk: floods. In this post, I dig into the issue of urban flooding – what are the causes, what are the dangers and impacts, and how can we better manage it?

What Causes Urban Flooding in the Bay Area?

Urban flooding is increasing in the Bay Area for four main reasons: California’s naturally variable precipitation patterns, climate change increasing precipitation extremes, population growth, and aging and insufficient infrastructure.

Natural Climate Variability of California

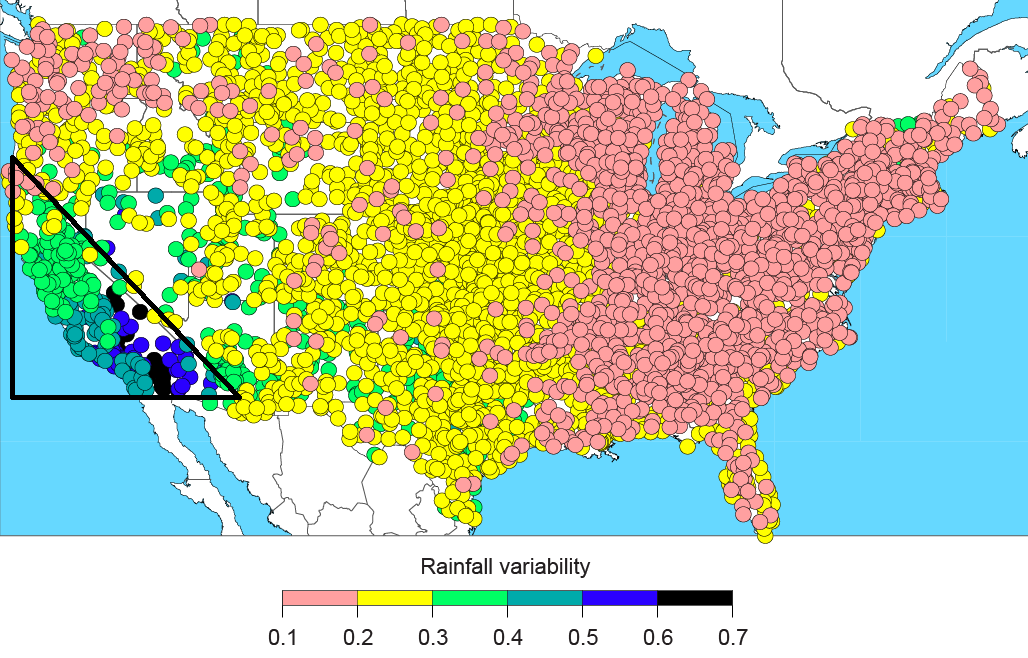

California is one of the most hydrologically variable places in the world, with long dry periods followed by a deluge of rainfall. Droughts and floods have influenced the history and development of California over the past several centuries, and paleoclimate evidence (like tree rings) shows that the region has experienced these dramatic swings from wet to dry for thousands of years. The map below provides a sense of that variability over the past 60 years; the dark green, blue, and back dots indicate that California has the biggest year-to-year rainfall fluctuations in the nation.

Coefficient of variation for annual precipitation at weather stations for 1951-2008. Larger values have greater year-to-year variability. Original source: M. Dettinger, et al. 2011. “Atmospheric Rivers, Floods and the Water Resources of California.” Water 3(2), 445-478. Image from the California Water Blog.

Climate Change Increasing Extremes

While dramatic wet-dry swings are not uncommon for California, climate change is turning up the dial on this variability, leading to what scientists are calling precipitation whiplash. While the amount of average rain may only shift slightly, we’re facing a big increase in precipitation extremes. One study predicts that by the end of this century, an extreme storm event that would typically only occur once every 200 years could begin happening every 40-50 years. The Bay Area Council Economic Institute estimates that a storm of that magnitude could cost $10 billion in economic damages.

“While the amount of average rain may only shift slightly, we’re facing a big increase in precipitation extremes.”

On top of flood events, because the Bay Area is largely made up of coastal communities, sea level rise means storm surges on top of higher ocean and bay levels will reach further inland. The State of California has instructed coastal communities to plan for a sea level rise of 55 inches by the end of this century. With 55 inches of flooding, much of West Oakland and Alameda Island will be underwater, and during storm surges and king tides, the waters will reach even further.

Population Growth

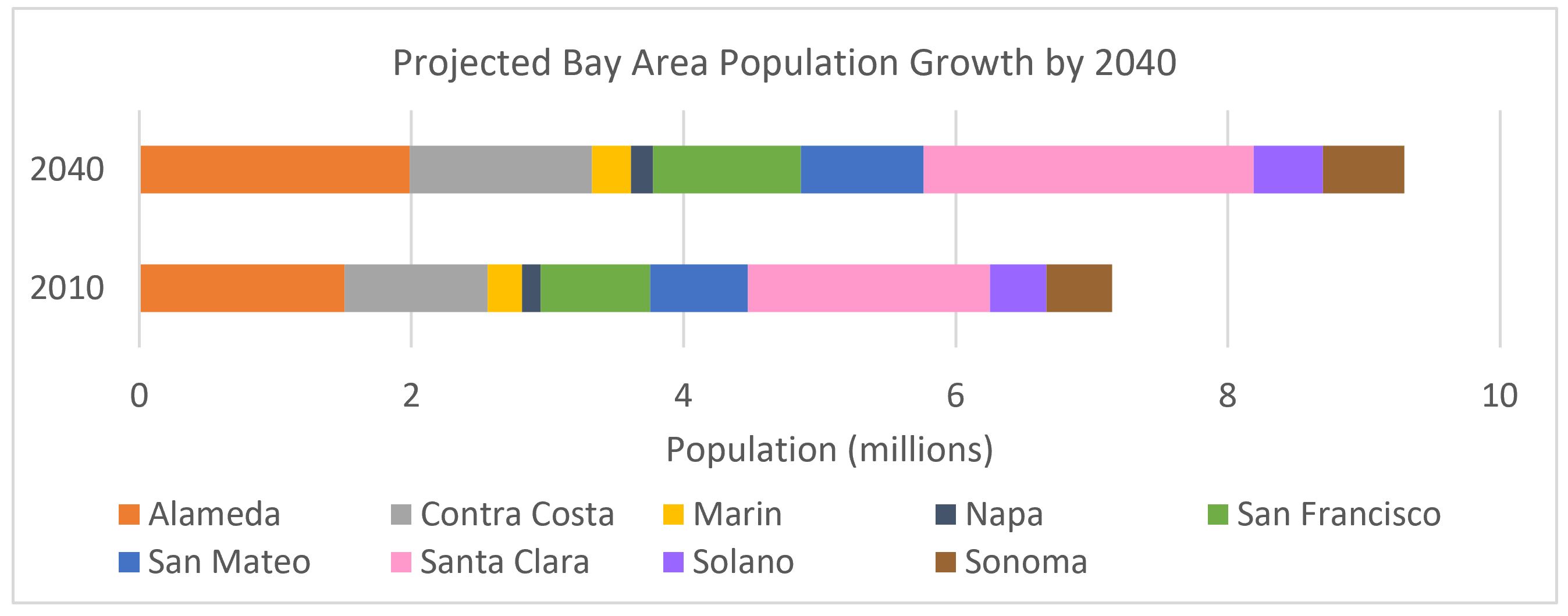

The rapid rate of population growth in the Bay Area will put more people at risk of urban flooding and sea level rise. By 2040, it’s expected that there will be two million more people in the Bay Area. Much of this growth will happen in counties with large shoreline and low-elevation areas like Alameda County and Santa Clara County.

Population of the nine Bay Area counties, actual in 2010 and projected for 2040. Data source: Association of Bay Area Governments and Metropolitan Transportation Commission. 2017. “Projections 2040: Forecasts for Population, Household and Employment for the Nine County San Francisco Bay Area Region.”

The Poor State of Stormwater Infrastructure

The infrastructure underlying cities in the Bay Area (and throughout the United States) is often designed to get rid of stormwater as efficiently and quickly as possible: pavement and sewers direct water into storm drains and send it out to the bay or ocean. This was originally done with the best of intentions – to prevent flooding and polluted water in our streets, and to keep our cities safe and clean. But these systems were built to a finite capacity; they can only handle so big a storm. And climate change is redefining the magnitude of our storms. Additionally, much of the infrastructure in place to manage big storms is at or past its functional lifetime and is deteriorating, adding to the lack of capacity to handle flooding events.

What are the Impacts of Urban Flooding in the Bay Area?

Two years ago, the Bay Area was inundated with severe rainstorms on the heels of a five-year drought. The 2017 storms were a prime example of the negative impacts of urban flooding: these storms submerged roads, shut down freeways, and delayed hundreds of flights out of San Francisco International Airport (SFO). Thousands of people in the North Coast and in San Jose had to evacuate due to flooding, and two people lost their lives.

In addition to putting property and human lives at risk, urban flooding impacts the ability of critical infrastructure to function as intended. Much of the Bay Area’s transportation system — airports, roads, highways, and railways — is concentrated along the Bay, making it more vulnerable to flooding from sea level rise and storm surges. Across the nine Bay Area counties there are over 500 miles of roads at risk of flooding in a 100-year storm event – and this is without factoring in sea level rise. Accounting for the sea level rise anticipated by the end of this century, we could see up to 1,500 miles of roads flooded.

Flooding on the Embarcadero in San Francisco in 2017. Credit: @burritojustice on Twitter.

Wastewater treatment plants are also at risk during big storms due to their shoreline locations – 83 percent of plants in the Bay Area are directly adjacent to the Bay. Compromised wastewater treatment infrastructure could lead to water pollution that threatens human and ecosystem health. Similarly, excessive stormwater runoff can overflow sewers and cause water pollution in the bay and ocean.

“Much of the Bay Area’s transportation system — airports, roads, highways, and railways — is concentrated along the Bay, making it more vulnerable to flooding from sea level rise and storm surges.”

When considering the impacts of urban flooding, it’s important to remember that those impacts are not distributed equally across Bay Area residents. Socially and economically vulnerable communities are often also most vulnerable to environmental risks, and have the fewest resources available to prepare for, react to, and recover from them. For example, West Oakland faces some of the greatest threats related to flooding. It is a low-elevation neighborhood with many disconnected low-lying areas, and has significant populations of low-income residents and people experiencing homelessness.

What Can We Do to Reduce Urban Flood Risk in the Bay Area?

Whether it’s this year, or another rainy season in the future, we know the Bay Area will face flood risks again. There are many ways to help Bay Area communities prepare for, adapt to, and recover from flooding. For example, improved weather forecasting can provide advanced warning of storm events, giving people more time to prepare. In addition, updating and improving existing stormwater sewer systems can help prevent overflows of polluted water onto the streets and into the Bay. Or, installing new protective infrastructure (like the levee in Santa Clara County, or the sea wall around SFO) can help defend communities from the most extreme storm events.

But one of the most exciting solutions is leveraging the powers of green space and nature to provide urban flood protection. This approach, often called green infrastructure, nature-based solutions, or low-impact development, can help to slow, spread, and sink water into the ground, rather than overwhelming stormwater infrastructure and polluting local waterways.

“California’s coastal cities have been described as ‘giant concrete bowls tilted toward the sea,’ and what happens when you pour water into a bowl? It fills, and eventually spills. We need to start thinking of and designing our cities more like giant sponges.”

California’s coastal cities have been described as “giant concrete bowls tilted toward the sea,” and what happens when you pour water into a bowl? It fills, and eventually spills. We need to start thinking of and designing our cities more like giant sponges: reducing the amount of pavement in flood-prone areas and replacing it with green space where water can soak into soils. This can happen at the scale of a single home – like having a rain garden in your front yard. It can happen at the scale of neighborhoods – planting more trees, restoring creeks and wetlands, and designing streets medians to collect rain. It can also happen at the regional scale, with larger-scale green infrastructure investments like engineering stormwater retention basins, constructed wetlands, and tidal marsh restoration. These kinds of strategies will increase the capacity of Bay Area communities to withstand heavy rain without severe damage.

Unlike traditional solutions like storm drains, sewers, and levees, solutions that incorporate nature can provide many benefits beyond just flood control. One important benefit is that green infrastructure can help us withstand California’s dramatic wet-dry swings by locally capturing water during the rainy season that can be used when the weather dries up. Research done by the Pacific Institute and NRDC showed that stormwater capture across the Bay Area and Los Angeles regions could provide up to 195 billion gallons (600,000 acre feet) of water per year, which is about the annual water use of the entire city of Los Angeles. Additionally, urban green space provides habitat to help animals survive city life, and can make people happier too.

“Unlike traditional solutions like storm drains, sewers, and levees, solutions that incorporate nature can provide many benefits beyond just flood control.”

While green infrastructure holds much potential for addressing urban flood risk, we know it is not the sole solution. The Bay Area needs a strategic mix of green and gray infrastructure – rain gardens and wetlands and pipes and levees – to be resilient to the increasing severity of storms.

Lastly, low-income and minority neighborhoods are likely to continue to be most impacted by urban flooding. But they can be part of the solution as well. It is critical that Bay Area leaders include vulnerable communities in their decision-making. This means focused outreach to communicate risks and response strategies to communities who speak languages other than English, or who may not have the time or means to attend informational meetings in person. It also means considering the unintended impacts to vulnerable communities of flood management solutions before implementing those solutions. Those who are already facing social and economic challenges are more likely to experience magnified adverse impacts from environmental risks like increased flooding, and may need extra outreach and resources to ensure resilience.

Take-Home Message

Urban flooding is worsening in the Bay Area for four main reasons: California’s naturally variable rainfall patterns, climate change increasing weather extremes, population growth, and aging and insufficient infrastructure. To address this problem, we need to redesign our cities to be more like sponges, capturing and soaking in or holding flood waters. This means improving and update our “gray” infrastructure (sewers and pipes) and investing in “green” infrastructure, like rain gardens, constructed wetlands, stormwater retention basins, and tidal marsh restoration. When making these decisions and investments, it is important to meaningfully involve vulnerable communities to ensure the solutions meet their needs and improve their resilience too.