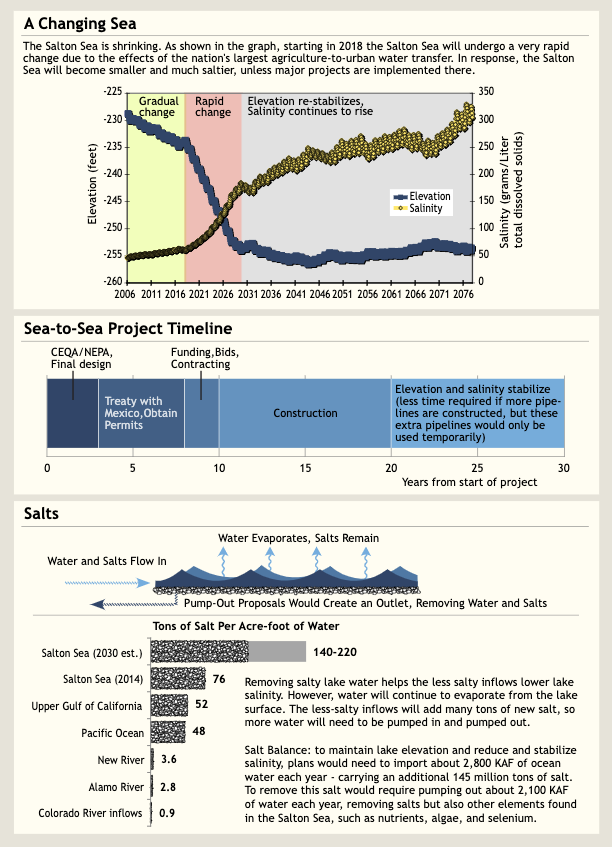

California’s Salton Sea fast approaches a tipping point, driven by declining inflows and the continued absence of mitigation or restoration projects. Salton Sea import/export plans, often known as “Sea-to-Sea” plans, have been proposed and promoted for more than 30 years to address this challenge. They come in a variety of different designs and routes but the general concept is this: raise and stabilize the surface of the Salton Sea and lower and then maintain its salinity.

To do this, Sea-to-Sea plans would augment the declining volume of water flowing into the Salton Sea by bringing in as much as 2.8 million acre-feet of water every year from either the Gulf of California or the Pacific Ocean – roughly the amount that flows through the All-American Canal. Because such ocean water will bring tens of millions of tons of new salts into the Salton Sea, such plans also need to either pump a lot of water out of the Sea, run multiple desalination plants at the Sea itself, or quickly turn the Salton Sea into a vast brine lake.

Sea-to-Sea plans would augment the declining volume of water flowing into the Salton Sea by importing water from either the Gulf of California or the Pacific Ocean. Because such ocean water will bring tens of millions of tons of new salts into the Salton Sea, such plans also need to either pump a lot of water out of the Salton Sea to export the millions of tons of salt, desalinate the water before it enters the Salton Sea, or run multiple desalination plants at the Salton Sea itself.

The Salton Sea is so large – currently covering about 330 square miles and filled with approximately five million acre-feet of water (an acre-foot is a quantity of water that would flood an acre of land one foot deep, or 325,851 gallons) – that such plans would need to import about approximately 2.8 million acre feet (2,800 KAF) of water to the Salton Sea each year, or more than twice as much water as runs through the Colorado River Aqueduct to supply L.A., San Diego, and Orange County. Import/export plans could cost $49 billion or more.

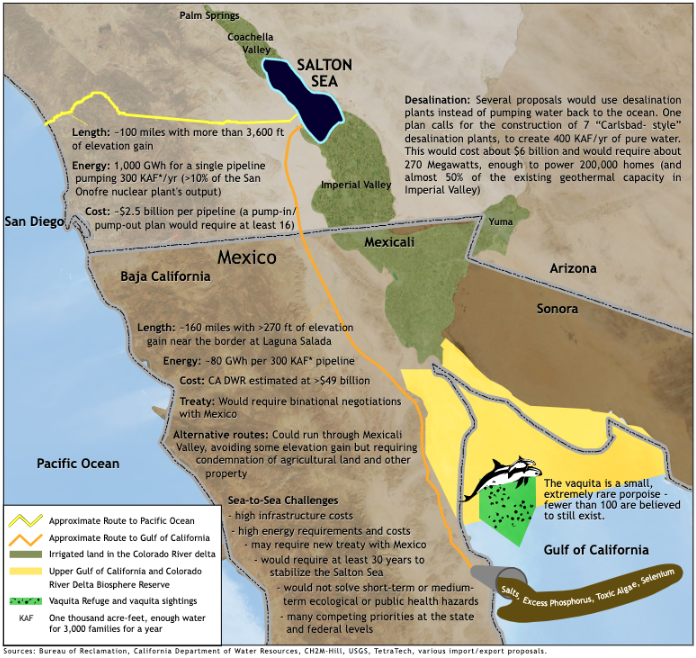

As described in the Sea-to-Sea video, there are two general routes by which ocean water could be imported into the Salton Sea: from the Pacific Ocean via the California coast, or from the upper Gulf of California via Mexico. The Pacific Ocean route would require more than 100 miles of pipelines and an elevation gain of more than 3,600 feet. Importing water from the Gulf of California would require pipelines running more than 160 miles, to extend beyond the internationally recognized biosphere reserve and the refuge for the endangered vaquita porpoise. A gulf route would require much less energy for pumping (though still about 300 feet of lift over the range north of Laguna Salada at the border), but would require the negotiation of a new treaty with Mexico.

Challenges

Sea-to-Sea plans face many logistical, financial, and energy challenges.

Designing, permitting, and acquiring rights of way for a project of this scale would be a tremendous undertaking that would require many years and multiple land use agreements.

The costs of constructing a hundred or more miles of pipelines or canals would be measured in the billions of dollars.

The additional energy demands of pumping tremendous amounts of heavy saltwater scores of miles and, in some configurations, up thousands of feet, would come at the same time that California seeks to reduce its carbon footprint.

Many of the proposed plans would require negotiations with Mexico, adding many unknowns to the equation, including the amount of time needed to come to an agreement.

Perhaps the greatest challenge, however, is the amount of time required for the plan to show results at the Salton Sea. As shown in the timeline in the infographic, even given the most ambitious, accelerated schedule indicates that Sea-to-Sea plans would not meet their own goals for at least 30 years. If a Sea-to-Sea plan were approved and adopted this year, the elevation and salinity of the Salton Sea would not stabilize until 2050, at the earliest. Such an approach would not solve the many short-term or medium-term problems of the declining Salton Sea, including the crash of the current ecosystem. It also means that public health would not be protected for a generation.

One of the biggest problems is that Sea-to-sea plans distract attention from feasible, practical plans that can be built quickly and can show results in the near future.

Although Sea-to-sea plans are intuitive and appealing, they are not the answer to the imminent collapse of the Salton Sea.