By Peter Gleick, President

The history of water development around the world, and especially in the western United States, is really a history of the construction of massive infrastructure, particularly large dams. As populations and economies expanded, the need to control, channel, and manage water grew, and large dams offered a way to provide energy, relief from damaging floods and droughts, irrigation water, and water-based recreation.

There is no doubt the construction of dams played a vital role in the past in supporting our growing economies, and some regions of the world would benefit from the careful development of new dams and related water infrastructure. But along with the benefits of dams came unexpected, understudied, or long-ignored costs above and beyond the narrow economic costs of building them. These costs include disruption of the ecology of free-flowing rivers, extinction of a range of aquatic species including key fisheries, displacement of communities, and destruction of cultural sites. Literally tens of millions of people around the world have been forced to abandon their villages and homes because of the flooding caused by big dams.

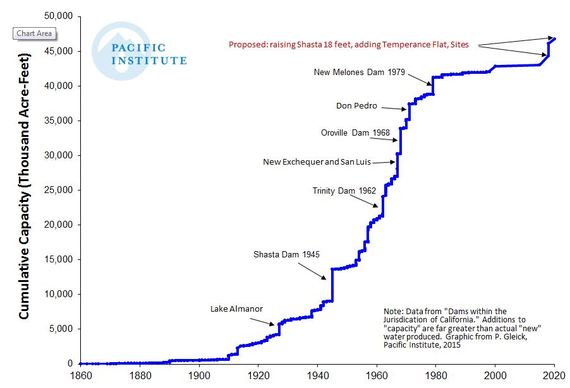

In the past few decades, there has been a growing awareness of the need to more carefully balance the potential advantages of dams with their negative consequences, and new guidelines have been developed for evaluating and reducing the risks of such projects to communities and the environment. For countries like the United States, especially in California and the western U.S., most of the best dam sites have already been exploited and massive government pork-barrel subsidies have disappeared, slowing the construction of new dams. Figure 1 shows the construction of new dams in California and the peak of activity in the middle of the last century.

Figure 1. Water storage capacity of California dams over the past century. (P. Gleick/Pacific Institute)

At the same time, there is a growing movement to remove dangerous, costly, and damaging dams and to restore–at least in part–some riverine environments and their fisheries. In the United States, according to American Rivers, nearly 1,150 dams have been successfully removed, including some large ones.

Despite this history, there is still pressure to build new, big dams and to ignore their human and ecological costs. In California, where thousands of big and small dams have been built, some politicians still call for more dams, despite extensive and compelling assessments showing that new projects are not cost effective, would have massive additional environmental and cultural impacts, and would not–in the end–do anything to resolve the state’s water challenges. This old-style thinking can be seen in the design of California’s 2014 $7.5 billion water bond, which included $2.7 billion for new storage and only $100 million for water conservation and efficiency, which could save far more water than any new surface storage project could ever supply, at far lower cost.

The poster child for this antiquated and misguided approach is the proposal to raise the height of Shasta Dam and increase the potential storage volume of its reservoir–California’s largest. Built in the late 1930s and early 1940s by the federal government, Shasta plays in important role in regulating flows in the Sacramento River and providing water supply to farms in central and southern California. Various proposals to raise the dam between 6 and 18 feet have circulated for many years, but there is significant opposition from some hydrologists, communities, environmental groups, and local Native Americans whose land is directly at risk. Recent legislation submitted to Congress would accelerate raising the dam by providing funds, reducing environmental protections, or bypassing existing review processes.

The problems with raising Shasta Dam epitomize the problems with big dam projects everywhere. The additional useful water that might be gained is far more expensive and far smaller in quantity compared to the water that would come from other approaches, especially improved water-use efficiency, local stormwater capture, and the reuse of high-quality treated wastewater. The additional flooding the dam would cause would violate the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which protects some of the state’s few remaining relatively undamaged rivers and streams, and it would further destroy some of the few remaining sacred sites and traditional homelands of the Winnemem Wintu people, whose lands were devastated by the original construction nearly a century ago. As noted in a letter recently sent to Senator Barbara Boxer and the California Congressional delegation,

“Raising the dam will harm the Winnemem Wintu people who have already been harmed by the dam. Shasta Dam flooded most of their sacred sites and traditional homelands, including their cemeteries. Raising the dam will flood out the little that remains. For a traditional people deeply tied to the land, further flooding would be worse than drowning St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican as they have no other sacred places to turn to.”

(“For a traditional people deeply tied to the land, further flooding would be worse than drowning St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican as they have no other sacred places to turn to.” Photo montage by P. Gleick 2015)

In the end, there are new, smart solutions to our water problems that don’t involve further costly destruction of our natural ecosystems and local communities. Let’s not apply 20th century solutions to 21st century problems.

This blog was originally published on the Huffington Post.