By Katie Porter at Brown & Caldwell, Darcy Bostic and Morgan Shimabuku at Pacific Institute, and Laura Feinstein at SPUR

This blog post was originally published on Meeting of the Minds.

Approximately 25 million people in the United States are served by water systems that regularly fail to meet federal safe drinking water standards. In addition, systems with poor water quality are more likely to serve low‐income and semi‐rural communities, as well as people of color. Internationally, other developed nations like Canada and Australia also struggle with delivering safe drinking water universally, particularly to rural, indigenous communities.

As technology for detecting contaminants and our understanding of the health impacts of contaminants improve, water quality standards become more stringent. More rigorous standards combined with increasing water quality challenges will make it even more difficult for systems with limited capacity to meet drinking water requirements. In particular, small community water systems (those serving <10,000 people) comprise the vast majority of systems with a history of long‐term health‐based violations.

The economic challenge of operating and maintaining a small water system is a large contributor to water quality violations. Assuming that there are certain fixed costs that remain approximately the same across systems regardless of size, it costs more per customer to operate and maintain a small system than a larger one. Best practices such as experienced managers and regular maintenance can be burdensome for small systems. Additionally, spreading operations and maintenance costs among fewer customers can make it challenging for water bills to remain affordable for all. As COVID-19 and the associated recession continue, customers are increasingly unable to pay their water bills, resulting in decreased revenue to water suppliers. This decrease in revenue exacerbates financial stressors on small systems.

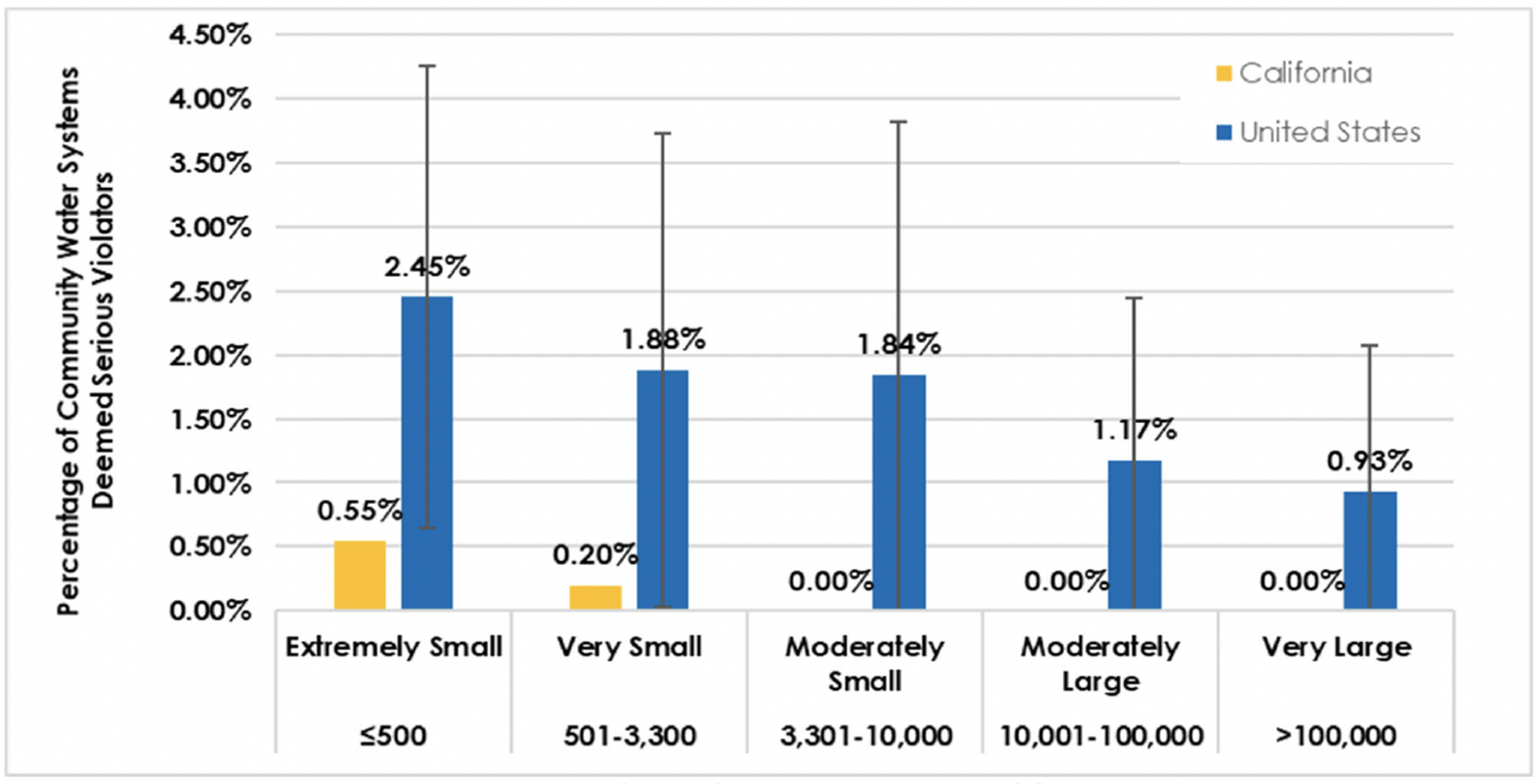

Large water systems are also challenged by many of these factors, however data show that nationally, less than one percent of very large systems experience serious, ongoing issues with meeting drinking water quality standards. This suggests that solutions are urgently needed to help struggling small water systems remain solvent and ensure their ability to deliver safe, affordable water to their communities.

California Urban Water Agencies (CUWA) and Pacific Institute are co-principal investigators for a Water Research Foundation (WRF) project, Solutions for Underperforming Drinking Water Systems in California. The findings from this work may also be applicable to other states wrestling with similar challenges. This article builds upon the discussion in the January 2020 article on this site, Equipping All Communities with Safe, Reliable Drinking Water, and provides several additional key findings of this work pertaining to:

- The challenges to California’s small drinking water systems, with a focus on those that are out of compliance with federal and state drinking water standards

- Solutions to address these challenges in California and beyond

Understanding California’s Drinking Water Violations

California has many small systems compared to other states. However, California has about the same percentage of underperforming small systems with problems delivering safe water as most other states (Figure 1). Thus, the lessons learned from characterizing and solving the problems in California may be transferable to other regions, nationally and internationally.

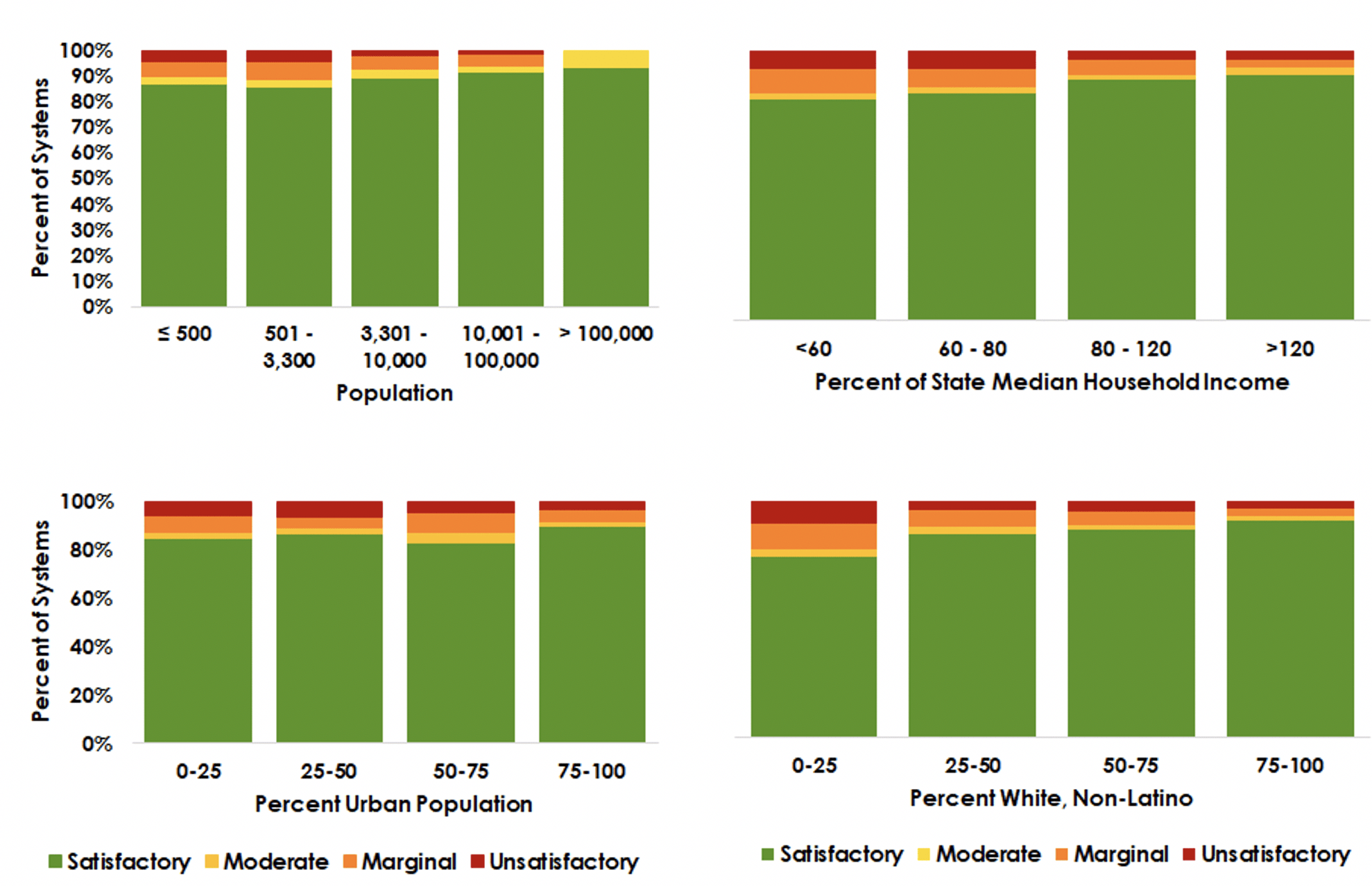

California’s underperforming water systems are primarily located in small, semi-rural, low-income, communities of color (Figure 2). The systems serving communities of color are four times as likely as white communities to have persistent water quality violations.

Many small water systems experiencing water quality challenges were found to be in violation due to three main contaminants: arsenic, uranium, and/or total trihalomethanes (TTHM). Arsenic and uranium are naturally occurring in groundwater, and systems in violation of these contaminants were mostly located in the San Joaquin Valley, where water supplies are typically from groundwater. The other common violation, TTHM, is a known byproduct from water treatment processes. Some contaminants that did not cause many violations during the study period (2016-2019) are likely to become larger problems in the near future as new regulations come into effect. Two examples are 1-2-3 Trichloropropane and Chromium VI, which are entirely or mostly caused by human pollution.

Solutions for California’s Underperforming Small Systems

Policymakers can advance their efforts to provide safe drinking water to all Californians in two ways. First, they need to continue efforts to “stop the bleeding” by preventing new unsustainable water systems from forming. Second, we need more comprehensive efforts to implement long term solutions for systems that are failing.

Broadly, we recommend the following high-level solution categories (See previous article for additional discussion):

- Operational solutions, including remote and contract operations

- Treatment solutions, such as facilities optimization, and point of use or point of entry treatment

- Source water solutions, including new internal and external water supplies

- Partnership solutions, such as physical or managerial consolidation and mutual assistance

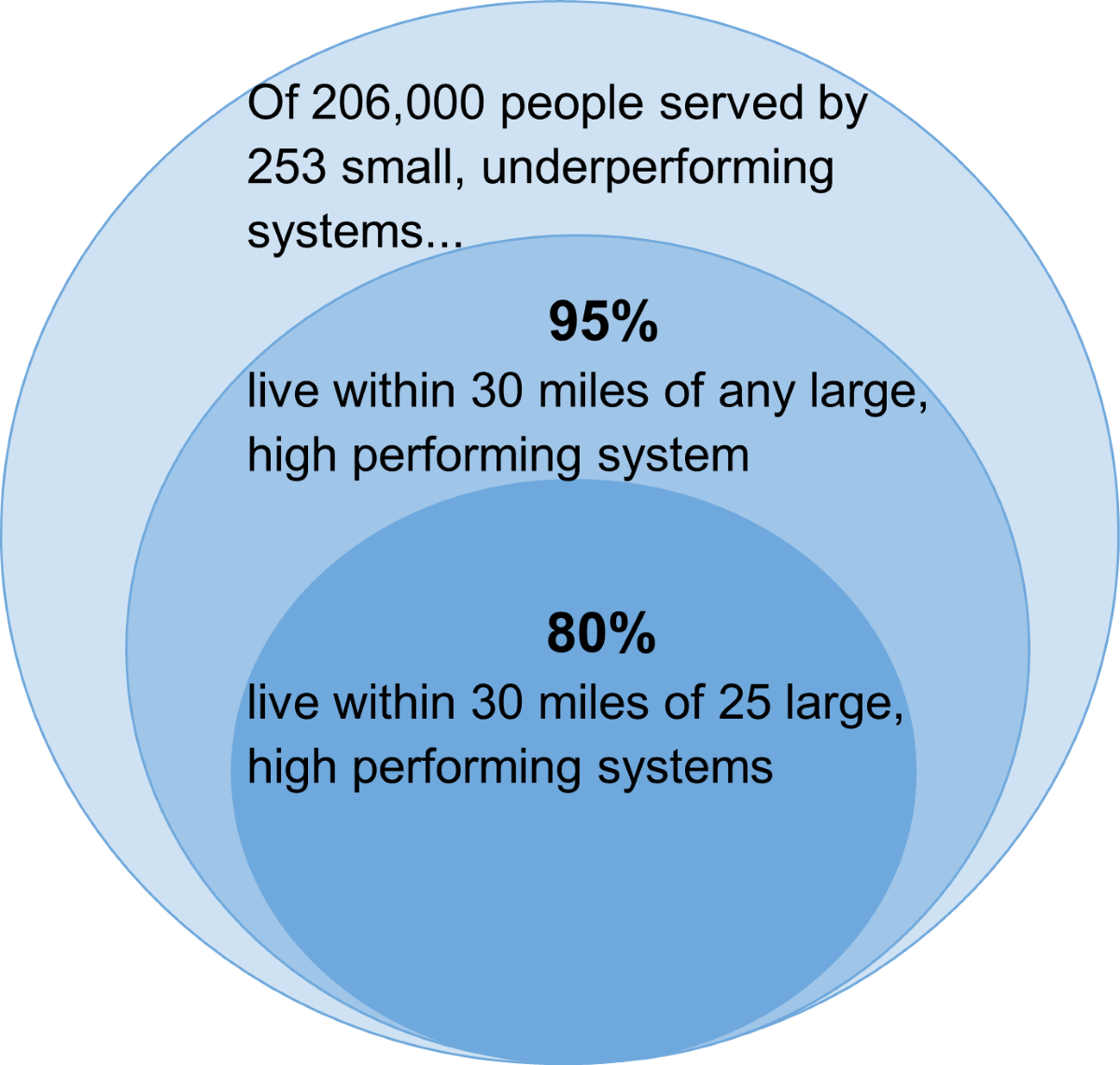

Of the solutions presented, partnership zones offer a high-impact opportunity for progress. Partnership zones refer to any form of cooperation across multiple water systems to improve services and efficiencies of one or more of the systems. Examples can include joint powers agencies, mutual aid/assistance, managerial consolidation, physical consolidation, or even informal cooperation. Two or more systems within 30 miles or less tend to be better candidates for managerial consolidation, such as allowing for shared staff and equipment, while two or more systems within three miles or less tend to be the best candidates for physical consolidation because of the sheer cost of building connecting pipelines.

In California, approximately 200,000 people are served by 253 small, underperforming drinking water systems. The vast majority of these small systems are within 30 miles of a large, high performing system. This suggests that regional partnership solutions can reach 95% of underserved Californians. Partnership zones developed around 25 of the state’s highest performing large systems could reach 80% of underserved Californians.

While partnership zones offer a set of innovative and practical solutions to many small water systems struggling to meet drinking water standards, financial incentives and support are needed to overcome the many barriers to forming a successful water partnership. Particularly challenging are cost and benefit inequities between the partner communities. Short‐term rate shock and long‐term rate increases, which often accompany a consolidation of two or more systems, are hard to sell to customers. Local communities are sometimes reluctant to give up authority over their water utility.

The process of learning what is sufficient to incentivize large high‐performing water systems to support nearby underperforming water systems is a major challenge, and some immediate strategies to facilitate water partnerships have emerged. For example, state or federal regulatory agencies could offer funding to supplement travel, incidentals, and labor required to evaluate partnership potential and implement consolidation. Another approach, which is currently in place in California, is to encourage water systems to pursue consolidation or regionalization through offering low- or no-interest loans for their infrastructure projects that provide additional drinking water supplies. In addition to financial support, legal remedies will also be needed to resolve responsibilities related to past violations and other obligations of the underperforming system.

In California, the policy groundwork, going beyond incentives, has been laid to ensure that the most vulnerable groups are not left without water. In 2012 the state committed to ensure that every person has access to safe, clean, and affordable drinking water. And, in alignment with this goal, two state-wide policies have been enacted; one that requires management of groundwater (the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act), and a second that created a program to identify and fund solutions for water systems and domestic well users currently without and at-risk of losing access to safe water (Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience, SAFER). The funds associated with these solutions are the state’s first-ever source for operations and maintenance for small water systems. Particularly, the severely impacted populations served by water systems with persistent water quality violations will benefit from state financial assistance to support them in developing internal capacity and provide a path to long-term financial sustainability.

Applications Beyond California

This body of work, published in September 2020 by the Water Research Foundation, provides information on the scope of the problem as well as practical solutions for California. Our hope is that these offer a blueprint for communities ready and able to take action through local and regional solutions. But more will be needed to address the full set of drinking water challenges existing in the state and beyond. Small drinking water systems in California are fortunate to have the new SAFER program crafting a set of tools, funding sources, and regulatory authorities to solve the complex problems facing small systems.

Unsafe drinking water is an urgent problem that disproportionately affects low‐income communities of color in California and across the U.S. In California, we’ve learned that the right environment and policies inspire stakeholders to come to agreement on prioritizing solutions that provide the best results based on each system’s unique problems. Improving water quality is more than choosing a technical solution. Community alignment and support, political willingness, and mutual agreement are all critical elements that, when combined with the right technical solutions, allow systems to thrive. In parallel with ensuring the right institutional and funding support systems are in place, we also need to choose and implement the most viable technical solutions for each system (which may in turn inform the support systems). Every system is unique, and some systems may require an immediate solution, while others may require a series of solutions implemented over time.