By Noah Garrison, Attorney with the National Water Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)

This post originally appeared at the NRDC Switchboard.

For much of California, 2013 was the driest year since the state started keeping records more than 150 years ago. In May, measurements of the Sierra Nevada snowpack, which normally provides about one-third of the water used by the state’s farms and cities (as well as by natural ecosystems) as it slowly melts through the spring and summer, were at only 18 percent of average for that time of year, and the state reported that it “found more bare ground than snow as California faces another long, hot summer.” Statewide, the average rainfall in 2013 was only 7 inches, far less than its long-term average of 22 inches, and the lack of precipitation poses a serious threat across the state—including placing communities at risk of running out of water (though this risk was thankfully reduced by rain, still below average, in February and March). Capturing that water when it does rain in our cities and suburbs can help communities increase their water supply reliability—so they have the water they need when it doesn’t.

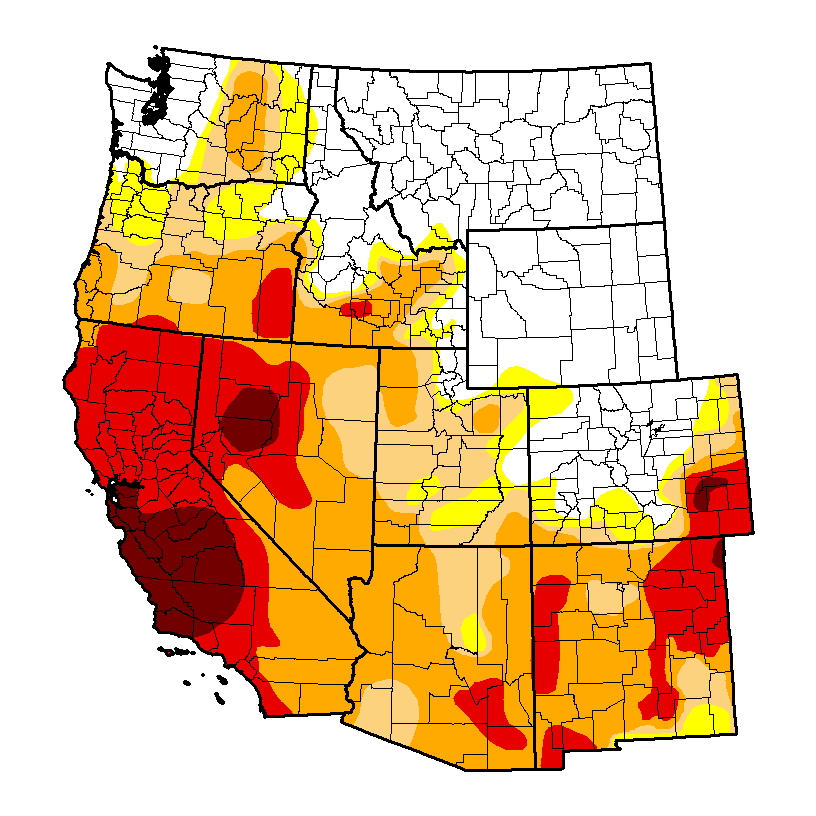

United States Drought Monitor for June 3, 2014, showing large portions of California in “extreme” (red) to “exceptional” (dark red) drought (http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/).

For decades, the way we’ve dealt with rain, and the stormwater runoff it produces, in our urban and suburban areas is to direct it away from development as quickly as possible—through curbs, gutters, and buried drainage pipes—to be discharged into the nearest body of water. And our cities and suburban areas produce a lot of runoff. A one-inch rain storm in Los Angeles County can result in more than ten billion gallons of runoff flowing through its storm drain systems, with most of that water ultimately ending up flowing out to the Pacific Ocean. Not only do we end up wasting all that precious water, but worse, we turn it into a source of pollution; as the rain falls on paved surfaces such as streets, parking lots, and sidewalks in our cities and begins to run off, it picks up car fluids, pesticides, pet wastes, metals, trash, and other contaminants it flows over, and carries this pollution with it to whatever river or beach it is dumped into.

But there is a huge opportunity to turn that rain and runoff into a resource for our communities. An analysis released today by NRDC and the Pacific Institute shows that capturing stormwater runoff for water supply across urban areas in Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area could increase local water supplies by between 420,000 and 630,000 acre-feet per year, roughly the amount of water used by the entire City of Los Angeles on an annual basis. By directing runoff to areas where it can soak into the ground and “recharge” groundwater, or capturing rain from rooftops in rain barrels and cisterns to irrigate landscapes or flush toilets, we can dramatically increase the amount of water available for local supply. Even during this period of extreme drought there is tremendous opportunity to make use of the rain that does fall, and in wetter years we can capture that runoff and store it in groundwater basins and aquifers, so we have the water we need when drought does return. Even better, in turning the rain into a resource, we reduce the amount of runoff, and pollution it picks up, that reaches our rivers and beaches.

A rain barrel at a residence in Santa Monica (photo credit: EPA/Abby Hall).

There’s a lot we can do to make use of the resources we have. For more information about the 21st Century water supply solutions for our cities, suburbs, and homes, which together can offer enough water savings and demand reductions to meet California’s water supply challenges, check out our Water Supply Solutions website.

Spreading grounds in Los Angeles County used to capture stormwater runoff for groundwater recharge (photo credit: Water Replenishment District of southern California).

Pacific Institute Insights is the staff blog of the Pacific Institute, one of the world’s leading nonprofit research groups on sustainable and equitable management of natural resources. For more about what we do, click here. The views and opinions expressed in these blogs are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect an official policy or position of the Pacific Institute.